Israel's systematic destruction of Gaza's educational infrastructure reflects a broader effort to dismantle the very foundations of its future. Palestinian media scholar Dr. Wesam Amer explains how this amounts to scholasticide.

Dr. Amer, could you explain what the term scholasticide means?

The term scholasticide has recently gained traction, especially within academic and activist circles, but it was coined some time ago. Professor Karma Nabulsi, a scholar at Oxford University, introduced the term to describe Israel’s systematic destruction of educational institutions in Gaza during Israel’s military operations in Gaza in 2009.

If the phenomenon is not new, why has it only recently become more widely recognized?

Although universities and educational facilities have been affected by every war in Gaza, it was only after October 2023 that people started to engage more deeply with what is happening to Gaza’s educational infrastructure.

Initially, there was a broader focus on the humanitarian crisis, and rightly so. But as the systematic destruction of universities and schools became undeniable, the term scholasticide began to resurface. This time with much more force. It is now being used to describe the targeted eradication of Palestine’s educational system, and it has been echoed by academics, activists, and even UN officials on the ground.

How would you define the term’s relevance today?

The term scholasticide sharpens the focus. It now more accurately reflects the reality in Gaza. It is not just about isolated attacks. It is about the intentional dismantling of education itself. Scholasticide shows how the destruction of education is not a side effect of war; it is a goal. The destruction of schools and universities is an attack on Palestine’s future, its hope, and the knowledge its people strive to build. As an academic, I find the term powerful because it frames devastation through an educational lens. While every sector is under attack, scholasticide allows us to analyze specifically the erasure of academic life: on the institutions, knowledge systems, and the students and professors.

625.000 students and 22.564 teachers have been impacted. Since October 7th, schools in Gaza have been closed. Students have not had a single day of normal learning. Professors cannot teach. Researchers cannot research. The infrastructure is gone. And yet, some continue publishing under the rubble, asking colleagues abroad to help edit their papers. It is a form of intellectual resistance, a way to say: “We are still here; we still believe in knowledge.”

Would you say this term is primarily used within academic circles, or has it reached a broader audience?

It certainly began within academia, particularly among scholars and institutions involved in academic activism. But now, it is moving beyond that space. We see it used more often in policy discussions, media reporting, and even by humanitarian organizations. It is becoming a vital term for understanding the depth and specificity of what is happening in Gaza.

Other regions experience attacks on education too, yet scholasticide seems particularly tied to Gaza. Why do you think this term resonates so strongly in the context of Gaza?

Several factors make Gaza's case stand out. First, there is the sheer scale of devastation. Israel’s war on Gaza has resulted in the near-total destruction of higher education. Gaza has twelve higher education institutions (eight universities and four colleges) and they have all been decimated.

We are talking about the deaths of hundreds of academics and thousands of students and teachers. The targeted attacks on schools have left almost nothing behind. There is no more infrastructure, no classrooms no resources. There is nothing left that allows any kind of educational process to continue.

Are there any links between attacks on universities and actual military targets?

Gaza’s entire education infrastructure has been destroyed. What does that have to do with Hamas? There is no justification for destroying a school or a university if the goal is to stop Hamas. Unless the real goal is to displace the population, to erase life in Gaza. There’s no military logic to this, only a political one, a destructive one.

Is the impact of this level of destruction felt beyond the educational sector?

Exactly. In Gaza, education is far more than the act of learning. It is deeply tied to identity, survival, and resistance. For Palestinians, education is a form of resilience. Our parents and grandparents have always emphasized its importance, even under blockade and war. It is seen as one of the few paths to dignity and hope.

In a place where the economy is largely paralyzed, where we have no access to natural resources where movement is severely restricted, education becomes the only viable route to financial stability. It is the only path many families see for their children to build a future. So, when education is targeted, it strikes at the very heart of our survival strategy as a people. From the second day of this war on October 8, 2023, Israel began targeting universities. The Islamic University and Al-Azhar University, Gaza’s two largest academic institutions, were among the first to be hit. That early and deliberate targeting set the tone for what was to follow. In the south, particularly in Khan Younis and Rafah, university campuses were temporarily converted into shelters for displaced people. But Israel also eventually destroyed those.

Were you targeted specifically as a scholar?

I did not feel singled out because of my academic role. I was not involved in any resistance activities. But I felt extremely restricted in what I could say. Speaking out is dangerous. We have seen what happens: outspoken academics like Dr. Refaat Alareer or my predecessor as a CARA fellow at Cambridge, Wiesam Essa, have been killed. Journalists have been targeted. It does not matter who you are; if you raise your voice, you are at risk. It is not just about resistance; it is about truth-telling. And that is dangerous. That is why I am deeply worried not just for myself, but for my family, friends, and colleagues still in Gaza. Anyone who speaks out could put their entire community at risk. We do not feel like this is a war on Hamas. It feels like a war on everyone in Gaza, to erase Gaza's existence.

Earlier, you described education as a form of resistance. In the face of all this destruction, is resistance still possible?

Yes, absolutely. The word is resistance, al-kalima muqawama. Speaking out is resistance. Writing is resistance. And the pen is also resistance, al-qalam muqawama. They can be more powerful than any other form of resistance. That is why we must raise our voices. We cannot allow ourselves to be silenced or erased, especially when all we are doing is exposing crimes and asserting our right to speak.

Some scholars describe this process as de-development or de-civilization. Is there a link?

A strong one. My mentor at Harvard, Dr. Sara Roy, has written extensively on de-development in Gaza, how Israel undermines every aspect of sustainable life. Destroying universities is part of that. Education is not just about learning; it’s a path to employment, to financial stability. When you erase it, you deepen poverty. You trap people.

Another important aspect is the Israeli accusations against Palestinian education, claiming that textbooks and cultural materials promote anti-Israel incitement or indoctrination. These allegations have impacted the Palestinian education system, especially primary education managed by UNRWA, which itself faces severe financial cuts from major donors.

Given all this, are there lessons for scholars watching this unfold?

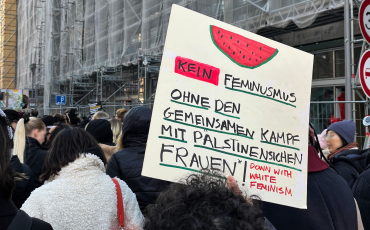

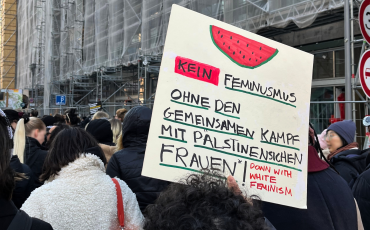

We need to revise our sense of moral responsibility. What is the role of academics? Of universities? In the West, there is a kind of paralysis; some genuinely want to help, while others hide behind questions like, “What can we do?” But I believe every professor, every university, knows exactly what they can do. They can give space to Palestinian scholars. They can pressure administrations to take moral stances. Universities can pressure governments. We have seen that in Spain, in the UK, and in the US, the student encampments have been powerful. The same goes for Norway, Sweden, and Australia. Academics and students are making a difference. Solidarity is not just about empathy or symbolic gestures. It is about action.

Holding Israel accountable for its actions is essential to prevent future crimes. Because Israel has largely escaped accountability, it has continued its siege, occupation, and military operations over the past 17 years, including repeated wars. If there had been real consequences, the ongoing violence we see today might have been avoided. Without serious and sustained pressure from the international community, the conflict is unlikely to stop.