While immigrant women are generally portrayed as victims of the patriarchal structures in their homelands and relationships, our author takes a closer look at the stories of some inhabitants of a women’s shelter in Germany.

By ratifying the Istanbul Convention, Germany has committed itself to the protection of women against all forms of violence, including domestic violence. It has pledged to provide low-threshold, specialized, barrier-free, and non-discriminatory support to those affected by violence, such as the provision of women’s shelters.

Immigrant women are disproportionately represented in women's shelters in Germany. Their limited access to resources, such as paid employment and networks, leads to a more complicated path when it comes to leaving - and saving their children from - violent relationships. Another factor which hinders their independence and leaves them exposed to violence from their spouses or partners is their residential status. For example, if a woman has come to Germany via a family reunification visa, she must stay married for at least three years in Germany before she can obtain an independent right of residence.

Immigrant women are largely absent in German media. A study demonstrates that between 2003 and 2017, immigrant women featured only in 12 to 26 percent of migration-related news articles. These women are generally represented as helpless victims of the patriarchal structures in their homelands and relationships. However, when we take a closer look at specific moments in the everyday lives of three immigrant women, their reality, agency, and resilience become more visible.

Taking a closer look at immigrant women’s experiences

M has lived in a women’s shelter in the city of D, which is 70 kilometers from her previous residence. It is not uncommon for women with three children or more to find shelter in cities or even federal states other than their previous homes. M is now far from her two older children, an 18-year-old daughter and a 20-year-old son, whom she had to leave behind to come to the shelter with her youngest 5-year-old. When I met M in her room in the shelter, she had already been living there for three months and was familiar with the stories of most of the other inhabitants.

M told me about J, who had stayed in the shelter for eight months until she had finally moved to an apartment: “After six months of looking for an apartment in the city of D and the most awkward conversations with private landlords, who were asking her why she doesn’t take up at least a part-time job, she started looking for an apartment in a smaller city and found one within two months. Do any of these landlords have the slightest idea about life in a women’s shelter with a 5-year-old with no childcare facility?”, she asked me.

Sitting in M’s room, I listen to her talk as she took out the insole from her child’s shoe, who had spent hours on the playground. A stream of sand pours out on the floor. Having left in a hurry, these were the only pair of shoes she had brought for her child. Since the weather has gotten warmer and the heaters in her room are not warm enough to dry everything quickly, M needs to wash the insoles that evening for them to dry up by the next day. All the grooves on the sole are filled with sand and mud, so she had to meticulously scrape each one with a small stick, and carefully to not make the shoes wet.

Psychological violence and disempowerment

“You are nothing and you do nothing” is what most of the women in the shelter have been told constantly by their husbands or male partners. They were made to believe that all the toil of family life falls on the husband-breadwinner. The psychological violence and disempowerment of these insults repeatedly come up in the conversations among the women in the shelter and seem to have left a footprint on their lives. However, not without resistance. Thus, M tells me: “We remind each other that we are here, we have made the huge decision to leave, so we can’t be nothing, can we?”.

“Your husband thinks you're just a gift from your home country”, another woman, A, quotes what an old friend had told her. A remembers vividly how she felt obliged to protect her child’s life from the violence caused by her husband’s substance abuse. All the disbelief in herself and the sense of loneliness in her marriage and a foreign country couldn't stop her determination to preserve her child's life and save them from her husband’s violent behavior.

Married life had begun with love for A, but later lacked emotional fulfillment. In the fourth language she acquired, A describes how the eager anticipation of her husband’s return from work had over the years turned into hiding in the child's bed to escape from the loveless sex. A had studied and worked in her home country, but then had to attend German language classes in Germany to obtain a certificate to work again. Her husband had constantly told her she would not get it.

The personal is political

While A had not deceived herself about her husband’s violence, she had remained hopeful that she could persuade the father of her child to undergo rehabilitation, or that he would at least accept that his delusions, fueled by drug abuse, were dangerous for himself, their child, and A. When A’s husband wounded himself with the kitchen knife while hallucinating that imaginary people were trying to harm him, it was a turning point for A. It had happened while she was traveling to her homeland with their child. When A returned and saw the evidence with her own eyes, she took the courageous step to leave.

The mental and emotional abuse A had endured in her relationship could not eradicate the urge to save her child and herself from the violence. As intimidating as it may be to leave one’s “home” in a foreign country whose language one has not yet mastered and without any income, A made that decision.

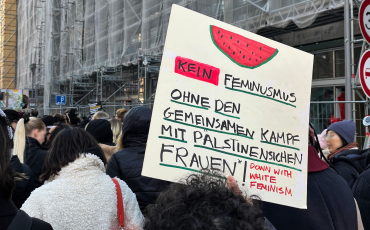

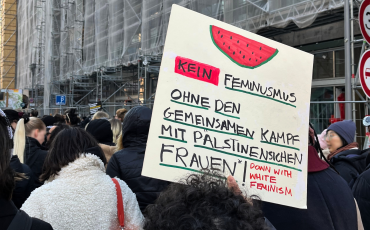

When witnessing the struggle of M, J, and A for a life free from violence and abuse, the slogan “the personal is political” comes to mind. Their seemingly individual endeavor is part of the collective global resistance and aspiration for a better, more equal world for all. Many women from Tehran to Chile, from Kabul to California, are fighting for this vision. These women show their children that they are not putting up with violence, neither at home nor outside of it, where they are often exposed to other forms of discrimination, such as racism.

The intersection of domestic violence and societal discrimination

The lives of immigrant women and mothers in Germany has become increasingly hard with the rise of the anti-migration discourse and corresponding policies in Germany, as well as the advancement of parties like the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD). While glorifying motherhood, the AfD is a patriarchal party that stigmatizes refugee and migrant mothers for the number of children they choose to have or the way they decide to dress. Thus, the intersection of domestic violence and societal discrimination makes the lives of immigrant women extremely precarious. Still, M, J, and A, just like many others, remain determined to achieve a dignified life for themselves and their children and build new “homes” in their host country.