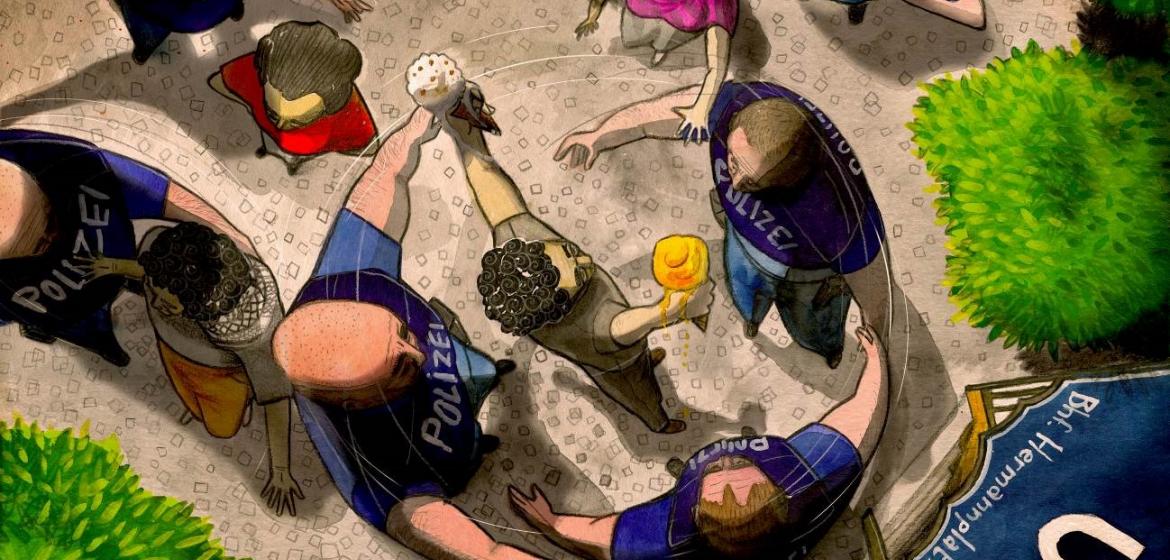

Strolling through Neukölln on Nakba Commemoration Day exposed our author to German police practices that provoked him to reflect on racism, democracy and his experiences in Egypt. An account of the battle over ice cream.

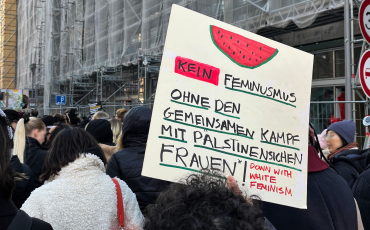

It was a warm sunny Sunday, a little past 4 p.m. on May 15th 2022, when I was walking with my friend Nadine through Neukölln, the neighbourhood I lived in in Berlin. We pushed our bicycles, discussing whether to go to a lake or Hasenheide, a nearby park. The best way to the park was through Hermannplatz. Which was also the planned location of a Palestinian protest to commemorate Nakba day. The protest had been banned by the German police, a decision later confirmed by German courts. The square was packed with police, a normal sight to people in the neighbourhood as Hermannplatz is the site of protests on most Sundays.

When I encountered this sight years ago, it was naturally terrifying. Experience with Egyptian police trained me that police presence means danger. But over the years, I let my guards down. My conditioning had worked, apparently. I headed to the square on May 15th walking through the hordes of police and protesters, on my way to the park.

Nadine and I had just crossed the street into Hermannplatz, when she came across one of her friends. Bahia, a German national of Moroccan roots, and two others, who were Palestinian. The conversation we tried to start was interrupted before it began.

Remniscing Egyptian Protests

Suddenly the police surrounded us within the square, and we found ourselves blocked in a blue-colored circle of policemen and women in full riot gear. “What are you doing here?” asked one of the policemen to which I replied in English, “I live around here.” Majed, one of Bahia’s Palestinian friends, replied in German, “Spazieren.” The scene reminded me of one of the earliest protests I had participated in, in June 2010, just outside the Ministry of Interior in Cairo. It was a protest calling for accountability of the police for murdering Khaled Said, a young man from Alexandria. I clearly remember not running when police approached.

At the time, the officer in charge put his hands on my friend Sherif and told his soldiers to “Cordon off these kids.” Police surrounded us from all sides with our backs to the wall. The police encircled various groups, some of whom were corralled in a full circle gasping for air. Despite those memories, I was aware this was not like Egypt at any given time. We had more space to breathe. The German police individuals were at least one and a half times the size of the poor Egyptian conscripts assigned to beat us, arrest us and, in years to come, murder us.

Attack

“Ausweis!” the burly German officers demanded of the five of us, we found ourselves encircled by a forest of blue uniforms. At least two or three officers assigned to each of us. “What’s the problem?” I asked calmly, trying to get a sense of what would happen next. The officer explained to me: “There was supposed to be a demonstration here, which was banned. We’re trying to make sure no one wants to demonstrate illegally now.” This was his non-answer; no matter how many times I reminded him, I was just passing through, inquiring why he would ask for my ID.

They said they would not charge us with anything but needed to collect our information before we were free to go. I thought the police would have a look at our IDs, return them and set us on our way. But the identification documents stayed with them; they asked us to remain where we were.

I was still holding my bicycle, talking to the police and was prevented from leaving. Meanwhile, a big hefty policeman was confronting Majed. He asked why he was being asked for his ID and claimed it was his right to be there walking like anyone else. The conversation escalated to the point where the policeman told him it was because he was wearing a Kufiya, the traditional Palestinian scarf. Majed protested and kept repeating that this was hardly illegal until the policeman got provoked enough to tell him it actually was. Understandably, Majed was livid.

The conversation escalated further. The policeman got impatient and suddenly attacked Majed, twisting his arms violently behind his back. Majed was in disbelief, shouting he could go by himself, but the policeman wouldn’t let up. Nadine, Bahia and the other young woman with us protested the violent handling of Majed. Then, other officers stepped in, physically shielding their colleagues’ aggression from any interruption. Majed’s day ended in the hospital, as his shoulder seems to have been seriously injured.

Minority Report

Nadine, a German citizen, protested the random ID check, our detention, and that her movement was limited. Watching the scene, I could not help but think that with her thick, dark, curly hair, she was not white enough. White bystanders were not surrounded or detained. Was this an internal or even official decision? I wondered what the exact directive was to these policemen and women – Surround anyone who looks Arab?!

We had been targeted calmly yet assertively. It was a little like in the film, Minority Report, where police look into the future crime to preemptively arrest and punish people before they had a chance to carry out these crimes. In our case, it was preemptive detention in case those Arab-looking people had a desire to protest. It was at that point that I started wondering: When does a protest start being a protest? Is it to shout slogans? Is it to show up with signs? Is it to dress a certain way? Is it to express a certain way? It was strange to realize, that our thoughts and the pigments of our skin and hair were being policed.

What a strange notion we have come to accept, that protests must be approved by the authorities you are protesting against. Many have argued that banning of this protest was unconstitutional by German standards.

“This is what has to happen”

My interaction with the police had been calmer than Majed’s and the others. The policewoman who had collected the identification documents assigned a large good-natured man to ensure I would not escape. “Am I being racially profiled?” I asked him bluntly. “Of course not”, he answered quickly, and I wondered about his quick response. How can he be so certain? Given that he does not have the authority to decide whether we can go or not? There was also no possibility of reversing their decision based on our answers or documents. I wondered, again, how this made sense to him.

He was friendly and soft-spoken, and I thought to myself that if we had met at a bar, we would possibly have had a nice conversation. Still, when I explained to him that such a practice was unjustified and reminded me of the Egyptian police practices, he got agitated and said, “Nevertheless, this is what has to happen.” To which I just responded: “Yes, of course, this has to happen; you have the guns. There’s nothing I can do.”

I don’t know if they realize that this is what it comes down to, the violence and the guns. Any escalation would give them the upper hand, not because of morality, justice or legality, but because of weaponry. Even with the notion that governments represent the people, the security service personnel deciding on the ground about our physical safety and freedom of movement are not elected. They stay in place, unelected, and for a large part, act with impunity. On the street, might is right.

A Scoop of Ice Cream

The police expressed their might by the sheer number of uniforms that flooded the square. Next to where we were held captive was an ice cream shop. There were chairs in front of the shop; some people had been sitting there just before we were surrounded. They didn’t look Arab and were not harassed. As we waited, I constantly asked if I was free to go, but I wasn’t. Time was no longer mine. I asked if I could sit, and was told I could, a permission that was later revoked. I wanted to test the limits of what I could do to alleviate this feeling of detention.

I asked the nice policeman if I could have some ice cream, and he said it was okay, almost shocked that I imagined he would deny me that. I marveled at how they allowed me some things that made it seem like I was free, but at the same time, they were restricting my movement and detaining me without reason. I stood in line for the ice cream and asked Nadine if she wanted some too. As she turned and headed towards me, she got into an altercation with her police chaperon, who objected to her walking away two steps without asking his permission. Apparently, I had been a good boy and was respectful to my masters at the time, so they didn’t scold me when I moved.

The ice cream seller was a very pleasant man. I only had to choose the ice cream flavor. When Nadine joined me after resolving her confrontation with the policeman, she decided on mango. She wanted two scoops, but the policeman allowed her only one. How terrible, the second scoop was denied. This negotiation of how many scoops we were allowed reflected their deep desire to show generosity while at the same time asserting their control, accepting or denying scoops.

I wanted the tiramisu flavor, but he had run out. It was perhaps the most disappointing turn of events. I picked caramel cookie flavor instead. Meanwhile, the shopkeeper asked the police to stay away from his store because their presence wasn’t good for his business. I have a lot of respect for his stance and how amicably he presented me with the ice cream and returned my change with a smile.

Nadine was surprised yet glad about my decision to buy ice cream at such a tense moment. I was focusing on the things I was free to do, such as having a conversation, directing a question, explaining myself, and even buying ice cream and perhaps sitting and eating it while I waited. After all, the stakes were not as high as in Egypt and I found solace in that.

“Platzverweis!”

Before we had the chance to sit down, we were finally asked to head to a police van to “verify” our information. As I crossed the street, the officer who had last confronted Nadine came up and thanked me for being calm about my detention. Perhaps having ice cream was a good move. After all, a willing prisoner is always more pleasant to the warden.

We later learned that checking our IDs had taken so long because they were discussing whether we all should be fined for participating in a banned protest or if they should just let us go. Our bodies were hostage to a decision in a police control room with nothing any of us could do to affect that decision and with no understanding of when and if we would be let go.

As were moved towards the special police vans that would supposedly check our information, we saw Majed inside one of the vans shouting, “They’re discussing which fake crimes they should charge me with!” We were worried about him.

After over an hour, they returned our IDs and expelled us from Hermannplatz (Platzverweis). I asked my escorting police officer what would happen next. He said, I may receive a letter with a fine, and that I could protest the fine by claiming I live close, so I shouldn’t worry. I wondered to myself why they would even do this, if they already knew that I shouldn’t be fined.

Nadine, on the other hand, was told they would not take further action, but contrary to what the police promised us, six weeks later we were charged with participating in an illegal assembly. Nadine’s charge sheet claimed she had arrived at 4.36 p.m., while mine claimed I had arrived at 4.10 p.m. Indicating that our charges were a political racist decision. Divorced from the testimony of officers who had interacted with us on the ground, carried out by the wasteful, unaccountable bureaucrats who are just doing their jobs mechanically. We do not know how much further they will disregard the reality of our story.

A Mandatory Conclusion

I have been part of numerous protests in Egypt in the past; I deliberately took part in events that endangered my life. Yet this is an instance where I had not done anything, nor was I aware that something would happen. This encounter should raise red flags to Germans. I can summarize the story: Over an hour of my life was stolen from me by a police force because I was present in a public place and was not white. Further effort tax money is wasted, pursuing us, further ignoring what had actually happened.

While many police personnel were amicable, they were made to enforce racist decisions and become complicit even if they did not hold racist beliefs themselves. It surprised me to know that police in Germany are rarely held accountable, and their testimonies most often weigh more than non-police individuals. Like in many other countries, their fellow officers will most certainly testify in favor of their comrades and lie for them if need be. These are worrying signs of an authoritarian state; I recognize them all too well from years of experience.

Despite the bitterness to come, I remind myself that this experience, luckily, did not leave a bad taste in my mouth. I will always look back and taste the caramel cookie ice cream flavor, courtesy of the German police. I look forward to returning to the ice cream shop in Hermannplatz and perhaps finding the tiramisu-flavored ice cream this time.