For too long, feminists in the global north have turned away from Palestine. In an attempt for change, this essay explores anger as a feminist tool for solidarity in the fight for liberation.

[Content Warning: This text mentions cases of gendered violence.]

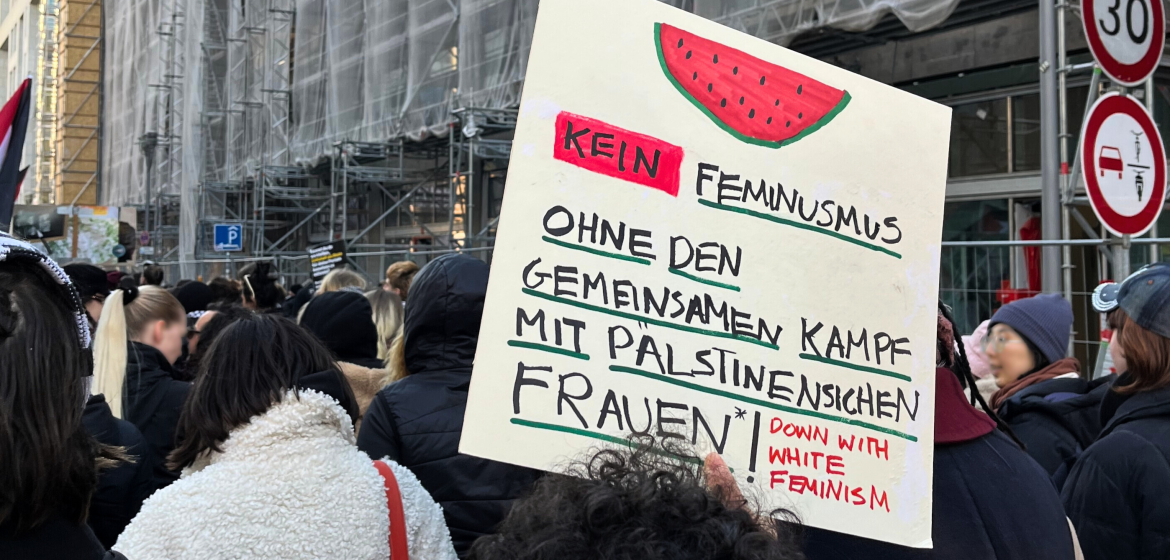

The ongoing genocide in Palestine has a huge emotional impact on me. Sometimes I feel sad, often I grieve, and many times, I am really, really angry. Despite the obvious reasons to be enraged in the face of total destruction carried out with impunity, I am particularly angry at the neglect of the Palestinian struggle by— predominantly white—feminists: One-sided, selective expressions of solidarity, divided 8th of March demonstrations, or the countless attempts of Pinkwashing Israel’s crimes by referring to its alleged queer-friendliness. In an attempt to reconcile with feminism and my own feelings, I began exploring how feminist anger can function as a liberatory emotion.

Feeling politics, political feelings

After two years of participating in different forms of Palestine solidarity work, I realized there had been little space for processing my own emotions. Of course, it is important to remain aware of one’s own privileges —in my case being white and German. This grants me the privilege, amongst many others, to advocate for and write about this topic without sharing the lived experiences of those affected by uprootedness and loss, and without facing the epistemic violence that suppresses, discredits, and delegitimizes their realities. Nevertheless, I came to understand that neglecting your own emotions in activism is not sustainable. Mental health challenges, especially when witnessing a genocide in real time, are valid.

To understand the power of feelings, we need to understand their political dimensions. When it comes to anger, its negative depiction is deeply rooted in colonialism. Recently, Emilia Roig, researcher, activist and bestselling-author, wrote: “At its core, colonial oppression rests on an unspoken but violent rule: the oppressed must never rebel.” Framing anger against oppression as “barbaric,” “uncivilized,” or “terror” is the outcome of fearing the resistance of the colonized.

This logic is closely linked to what scholars refer to as embedded feminism—a term coined by Krista Hunt. It describes self-proclaimed feminist goals in politics failing to be feminist in its implementation, as they serve merely as a pretext. Anthropologist Lila Abu-Lughod, for instance, elaborates in her paper how North American feminists called in the 2000s to “save Afghan women”. In reality, they denied them their agency, fuelled the demonization of Afghan men, and thus obscured the imperial violence of the U.S.’s so-called “War on Terror”, which posed the biggest threat to Afghan women’s lives at the time.

Colonial violence and its gendered dimensions in Palestine

Similar narratives echo throughout Western feminist discourses on Palestine. In a recent article, the political scientist Nicola Pratt and others highlight the ongoing colonial legacies entangled with feminism: Palestinian women are often portrayed as “oppressed” and suffering under “a patriarchal, conservative society.” The broader context of the ongoing struggle against settler-colonialism and life under Apartheid rule is ignored, and attention is diverted from the gender-based violence perpetrated by Israel, thereby upholding these very structures of oppression.

The root of violence against the Palestinian people lies in the settler-colonial character of the state of Israel: From the Nakba, the forced expulsion of around 750.000 Palestinians in 1948, the implementation of a military occupation and Apartheid rule, culminating in the current genocide in Gaza. It further manifests in the 2018 adopted Jewish Nation-State Basic Law, rendering Palestinian self-determination in Israel impossible.

Palestinian women[1] face numerous forms of systematic gendered violence, ranging from harassment at checkpoints to sexual assault in Israeli prisons. This is also referred to as “Reprocide.” It is evident in the unprecedentedly high rates of miscarriages due to the lack of hygiene, and in targeted attacks on health infrastructure, such as the airstrike on the Al Basma IVF Centre, which destroyed thousands of embryos.

No national liberation without the liberation of women

Women have always played an integral role in the Palestinian liberation struggle. In 1965, they founded the female branch of the Palestine Liberation Organization, the General Union of Palestinian Women (GUPW). And especially after the 1967 war, women also took part in armed struggle, amongst them prominent figures such as Leila Khaled.

For many politically active women, the question of national liberation was intertwined with the struggle for equal rights and the liberation of women—grounded in the understanding that justice and self-determination are fundamental. May Sayegh, a founding member of the GUPW who advocated for the arming of women in popular resistance, is quoted in the aforementioned article:

“Arab resistance should not stop at liberating occupied Arab land. Resistance should go beyond national independence to also target imperial interest, stopping the partition of the Arab world, divisions based on sectarian, national and tribal lines, and fighting discrimination against women and the exploitation of humans by humans.”

Reclaiming anger, resisting erasure

As I delved deeper into the topic of anger, I came across several examples of angry feminist resistance. One piece that deeply moved me was the poem “Shades of Anger” by Palestinian spoken word artist Rafeef Ziadah. In a radio interview, she recounts how, during an on-campus protest, a Zionist counter-protester kicked her in the stomach and said: “You deserve to be raped before you have your terrorist children.”

The poem was her response: “And did you hear my sister screaming yesterday, as she gave birth at a checkpoint with Israeli soldiers looking between her legs for their next demographic threat? Called her baby girl Jenin.” You can—and should—listen to the full poem here:

The poem emphasizes the female body highlighting the duality of colonial violence: on one hand, colonial violence is inscribed onto women’s bodies; on the other, it shows how women resist erasure with those same bodies. To say it in Ziadah’s words: their bodies are literally and metaphorically birthing resistance.

Anger as a generator for resistance and hope

Exploring anger, allowing it to take up space, and trying to reframe it felt right. Instead of feeling numbed by it, I came to understand its transformative potential. Connecting all of this to a feminist framework seemed like a small personal compensation; a reminder that, despite my deep disappointment in the discourse on Palestine, there are, and always have been, feminists out there who pave the way towards a more just future. It brought back something that, on a good day, could almost be called hope.

Hope. What a word in times of injustice and destruction. And yet, not losing hope is the most revolutionary act. Without hope for a brighter future what is there even left to fight for?

Therefore, I want to close with words of author, scholar, and self-proclaimed “feminist killjoy” Sara Ahmed:

“Solidarity does not assume that our struggles are the same struggles, or that our pain is the same pain, or that our hope is for the same future. Solidarity involves commitment, and work, as well as the recognition that even if we do not have the same feelings, or the same lives, or the same bodies, we do live on common ground.”

Learning from Palestinian Feminists, it is time to finally understand that systems of oppression, be it colonialism, racism, or patriarchy, cannot be fought in isolation. Feminism without Palestine is therefore just a perpetuation of oppression in disguise.

[1] Throughout this article, I am using the binary terms “women” and “men.” While in theory, the struggle described includes all FLINTA* people, the limited scope of this article does not allow for a more nuanced discussion of the specific struggles faced by, for example, queer or trans people. Nevertheless, I want to emphasize that by “men” and “women,” I am referring to socio-political categories rather than individual lived gender identities.