In the maelstrom of images, news, and social media posts full of despair, pain, condemnation, and calls for solidarity, questions pop up. Questions about humanity, the value of individual lives, and the right to have rights.

A flood of images, we pretended to have forgotten, strikes back. It re-opens the gates of hell on earth. One million people are commanded to leave their homes in Northern Gaza. Neither 'how' nor exactly 'where to' are areas of concern. Even the so-called safe routes to the south are being bombed. The great escape is supposed to take place amidst ruins, in one of the most densely populated territories of the world, besieged and tyrannized for decades, deprived of water, food, and medical supplies since the outbreak of the war. A ground offensive is likely to follow. Some voices in Israel suggested their displacement to Egypt; a biblical exodus in reverse without a promise of salvation. Or it is rather a salvation in reverse that dwells on resolving one of the longest ongoing political conflicts by uprooting or liquidating an entire population. It is still unclear whether the Egyptian authorities are willing to open the border crossing, and if so who will be entitled to enter or stay, and for how long.

I have questions, many questions.

Are these acts of siege, forced starvation and displacement included in the “unrestricted solidarity to Israel” and the rights of nation-states to defend themselves? Are these acts a part and parcel of what is been politically framed by the German government as “internationally recognized” rights? How can we conceive of the notion of “rights” under these circumstances? How can this recognized right to self-defense be reconciled with acts that evidently stand in violation to international humanitarian law? Are rights confined to those who are subjects of a sovereign nation? Are Palestinians in Gaza a bunch of people who do not have “the right to have rights” as Hannah Arendt notably put it, because they are not subjects of a sovereign nation in the first place?

How come that we are urged to condemn – and condemnation is here morally rightful – violent acts of militant infiltrators, debarred from the framework of legality, and at the same time to attest to such acts of state violence as legally rightful - although condemnation here too is supposed to be morally rightful? How can we survive in a world in which the void between legality and morality is becoming insurmountable? How can starving and displacement be legal, while calls for support with a besieged and bombed population are illegal? How can acting legally become synonymous with moral failure and acting morally subject to legal policing and censorship?

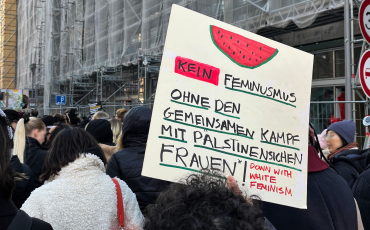

Calls for solidarity raise new questions

In the same moment, where friends and acquaintances in Germany are being violently silenced, threatened and some brutally beaten up for articulating their solidarity with the people in Gaza; in the same moment where the constitutional right of the freedom of assembly is repealed to delegalize protests in support of Gaza in Berlin; in the same moment where my Arab friends are reporting of racial profiling, random search and arrest in Neukölln by the police, the “Free” University of Berlin is demanding from “all university members to demonstrate solidarity with our Israeli friends and all who fall victims of the violence unleashed by Hamas.”

Does solidarity with friends include the validation of the above-mentioned forms of state violence and acts of forced displacement? Are Palestinians included in the “all” of “all who fall victims”? And if so, why so; what does it mean to designate them as part of the “all’ that comes after “friends”? Is it to denote their losses as collateral pain to the violence that legally deserves solidarity? What does it actually mean when an academic institution in a liberal democratic state, whose mission is to produce knowledge freely, compels all its members to demonstrate solidarity? Is that not also to compel all of them to feel and show affection in a specific way? Is it then rightful when members of the university feel neutral? Is it rightful when they feel pain for those not recognized as friends, grief for losses deemed collateral losses, rage against forms of violence deemed legal?

Stop and think

Various calls for solidarity and condemnation from both sides I came across have been embellished with phrases like “without ‘when’ or ‘but’”, defying contextual framing and historical situatedness. It is as if understanding violence is synonymous to its justification, as if political responses are conditioned upon the erasure of certain histories, as if virtue in the face of evil is to stop thinking. For Arendt, the opposite of this is correct. To act morally is to “stop and think” and evil is precisely the failure of reflective thinking, the incapacity to pursue a dialogue between one and oneself.

I truly grieve for the losses on both sides. Because each loss is equally worth of grief in its own right. I grieve for the bereaved mothers and fathers, for the terrified children, for the homeless, the wounded, the disabled, for the fearful and disparate. I grieve and cannot stop thinking. I cannot stop mulling over the ‘when’ and ‘buts.’ I cannot stop wondering, whose pain counts and whose pain does not. I cannot stop asking how inhuman we should be in order to be legally humans?